Nick Waterhouse: Don't Call Him Retro

“I had three horns last night, which is always nice. Can’t always afford that. It sounded really big.” Nick Waterhouse is recalling the May 10th show at Eagle Rock Center for the Arts, commemorating the release of his debut album, Time’s All Gone. The 25-year-old Orange County native’s show was sold out.

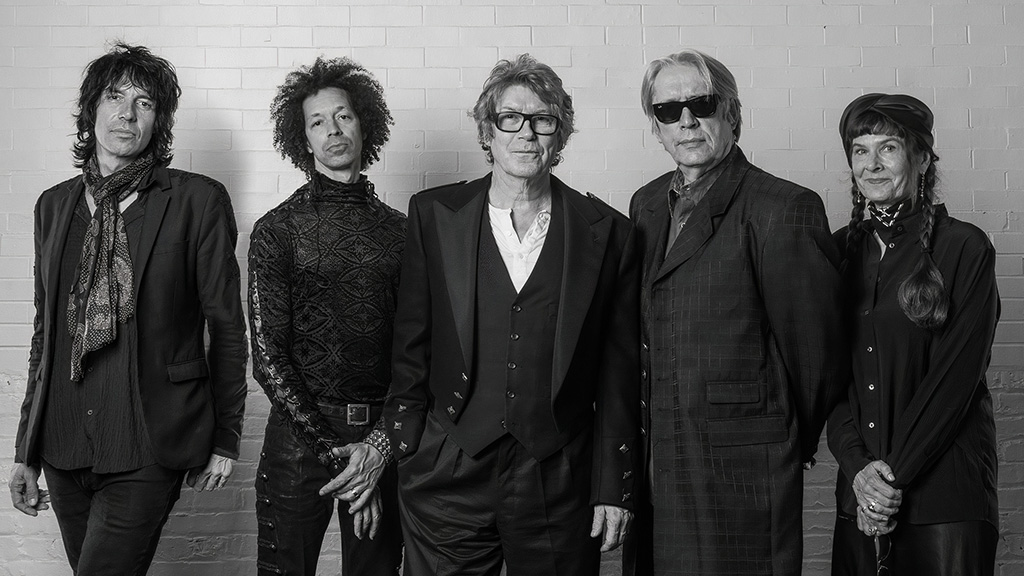

Waterhouse’s style has been called “retro,” compared to early ‘60s R&B, inspired by rock’n’rollers like Chuck Berry and Ike Turner. Even Waterhouse’s appearance, with his vintage getup and Buddy Holly frames give him the swagger of a mid 20th century hipster. To top it all off, Waterhouse records all analog, on tape with no computers present in the studio. He’s purposely avoided digital in favor of pre-1970s era microphones by Sony American and RCA, and other equipment that was standard stock in recording studios before it was replaced by ProTools.

“The equipment I use is at a studio called The Distillery which is in Costa Mesa,” Waterhouse Says. “I use it because I like how it sounds, but I only learned how to use that stuff.” The Distillery is also used by label-mates the Allah-Lahs, a band that has made their name among the scene of throwback surf-rock and psychedelic inspired California garage rock bands like the Tijuana Panthers, Shannon and the Clams, White Fence and Ty Segall, all of whom also record only on analog. While Waterhouse’s debut record sounds unlike the productions of those bands, the concept of recording on analog and the raw aesthetic it offers are becoming more popular and desirable. Their common ground lies in their sheer confidence of creation, and their fearlessness of, as Waterhouse says, “being irrelevant for playing something that people might consider redundant or dated.”

When it comes down to it, the sound that analog recordings create simply resonate with Waterhouse.

“The records I like were recorded that way,” he says. “I think that there’s no point in trying to spin gold out of cotton, if you have the gold there.”

The complex choices that digital recording presents can water-down the creative process, he says. “It gets you away from thinking about the song and the performance and people actually being together when they’re playing and sort of finding that place, that’s the thing that I like about playing music, when everybody hits something together and you feel totally electric.”

Despite his recording methods and a clear inspiration from 60s R&B, Waterhouse insists that you do not call him retro.

“I think that’s a term that is often tied to people that are impersonating something,” he says. “Obviously, if you look at its Greek root, it’s like backwards, regression. But the thing about music to me is that it’s a non-linear thing. Recorded sound is amazing because everything is regressive. Any time you listen to a song, you are immediately summoning this moment.”

That exact idea is where many so people find their satisfaction in music, in reliving the electricity of pleasure, loneliness, or nostalgia that is evoked through three or four minutes of sound. That magic in the preservation of a moment, bound by time yet timeless, is also why Waterhouse believes humans decided to start recording music in the first place. Creating something very fresh and new that was inspired by creations from another time in history is at the heart of the brilliancy of most artists, and music is no exception. There’s no rule stating that a person can’t find sparks in music that was recorded in the past, or that music written in the 1950s or the 1850s can’t be current by being heard in a new way by a new audience.

“I am inspired by a lot of records that were released a long time ago,” Waterhouse says. “but I guarantee you that most people haven’t heard them, the same way I hadn’t heard them. It was exciting for me and new for me to hear a lot of these tunes.”

Now residing in Los Angeles, Waterhouse says that Time’s All Gone was directly inspired by San Francisco and the years he spent living here.

“It was all just really feverish,” he says. “The general atmosphere of it is reflective of that time that was sort of a lot of fun but also a lot of unhappiness and a lot of tribulations, both in my personal life and trying to be a musician. It’s a fair representation of what I’m all about and what I wanted to hear.” His favorite record store in the city, a spot where he spent much of his time while he lived here, is Rooky Ricardo’s Records in the lower Haight. “I walked into Rooky’s eight years ago in June, when I was 18, and I eventually ended up working there, hanging around. It’s a place that I don’t think is like anywhere else in America. I think that its a treasure.” In addition to being an awesome record store where people can dig through the stacks and score three 45’s for five bucks, it’s also Waterhouse’s home base in San Francisco. “Rooky’s and the people there are really at the heart and soul of helping me understand my place in music and what I really like.” Waterhouse’s show at the Verdi Club in San Francisco on June 6th also marks the shop’s 25th anniversary, and he has personally dedicated the show to the crew at Rooky’s. DJ Carnita, DJ PriMo, and DJ Matt B, all playing opening sets at the Verdi Club on the 6th, were also hand selected by Waterhouse for the community they all shared at Rooky’s, or Hard French, or the San Francisco music scene in general.

Time’s All Gone is a wonderful representation of what Waterhouse has to offer to the current musical community, in California and elsewhere. His vast knowledge of music history and his straightforward, intelligent way of addressing his musical aesthetic just go to show that the record is not only a revelation for current audiences, it is an offering of a new way to look at things in our world as elements that can be re-imagined, reformed, or drawn upon to create something fresh, current and timeless.

Nick Waterhouse plays with support from DJ Carnita, DJ PriMo, DJ Matt B, and a special guest of honor from the Rooky Ricardo’s crew at the Verdi Club on June 6th. The show starts at 8pm and tickets are $12.

Nothing wrong with a little bit o’soul.