Tue February 26, 2019

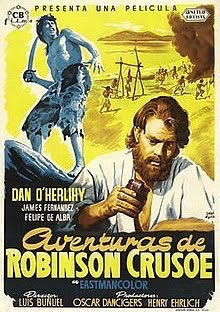

THE ADVENTURES OF ROBINSON CRUSOE (1954)

SEE EVENT DETAILS

at San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) - closed

(see times)

George Pepper co-produced the film with Russian expatriate Oscar Dancigers under the pen-name “George P. Werker” to skirt the blacklist. (It was Dancigers who first talked Buñuel into coming to Mexico to make films.) Defoe’s original novel, Robinson Crusoe, praises the virtues of colonialism, dehumanizing the colonized as mere “savages” and reinforcing a hierarchy between master and slave. Director Luis Buñuel and writer Hugo Butler (aka Philip Ansel Roll) subvert these themes.

Buñuel’s film Las Hurdes was banned in Spain from 1933-1936. Fascism in Spain drove Buñuel to seek work in the United States, only to be subtly blacklisted there as well, before he landed in Mexico. Since Pepper and Butler were blacklisted expatriates as well, the trio’s critique of Defoe’s glorification of conquest is so covert at times, it could be misinterpreted.

Buñuel, Pepper, and Butler’s portrayal of British aristocrat Robinson Crusoe’s shipwreck and isolation on a deserted island echoes the story of the cold war exiles marooned in Mexico. Departing from Defoe, Butler focus on Crusoe’s loneliness, particularly after the death of his dog Rex, as a central theme, echoing the marginalization of the Hollywood exiles. Author and historian Rebecca Schreiber points out, “his entrapment on the island is represented here visually by his inability to walk off the screen.”

The original book begins and ends in Europe, but the film begins and ends on the island. Here, a humanized and often more logical Friday rescues Crusoe from his loneliness and isolation. Also departing from Defoe, the later appearance of some mutineers elicits a comment by Crusoe about the most precious thing in life: community—exactly what enabled the cold war exiles in Mexico to not only survive, but thrive.

Though the internationalist exiles in Mexico often had to hustle and pool resources to make ends meet, they were still better off than their Mexican compatriots. Some expatriates had full-time maids, large living quarters, and cooks. These contradictions emerge as self-criticism in the disturbing understated colonial attitudes inherent in The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe.

In his autobiography, Buñuel writes that he “became interested in the story, adding some real and some imaginary elements to Crusoe’s sex life as well as a delirium scene where he sees his father’s spirit.” Characteristically, Buñuel underscores some absurdities in religion with an exchange between Friday and Crusoe, in which Friday seems the more rational. Slowly in the film, Crusoe gives up on his table manners and religious customs which make no sense in the isolation of an island, exposing them as irrational societal conventions. It is only when Friday arrives that Crusoe sees it as his paternalistic duty to teach these same manners and customs to Friday. Unlike the pat definitive Hollywood ending, The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe ends with the surreal barking of Crusoe’s dead dog, harkening to PTSD, delusions or a haunted future. All of these details are characteristically “Buñuel.”

show less

Buñuel’s film Las Hurdes was banned in Spain from 1933-1936. Fascism in Spain drove Buñuel to seek work in the United States, only to be subtly blacklisted there as well, before he landed in Mexico. Since Pepper and Butler were blacklisted expatriates as well, the trio’s critique of Defoe’s glorification of conquest is so covert at times, it could be misinterpreted.

Buñuel, Pepper, and Butler’s portrayal of British aristocrat Robinson Crusoe’s shipwreck and isolation on a deserted island echoes the story of the cold war exiles marooned in Mexico. Departing from Defoe, Butler focus on Crusoe’s loneliness, particularly after the death of his dog Rex, as a central theme, echoing the marginalization of the Hollywood exiles. Author and historian Rebecca Schreiber points out, “his entrapment on the island is represented here visually by his inability to walk off the screen.”

The original book begins and ends in Europe, but the film begins and ends on the island. Here, a humanized and often more logical Friday rescues Crusoe from his loneliness and isolation. Also departing from Defoe, the later appearance of some mutineers elicits a comment by Crusoe about the most precious thing in life: community—exactly what enabled the cold war exiles in Mexico to not only survive, but thrive.

Though the internationalist exiles in Mexico often had to hustle and pool resources to make ends meet, they were still better off than their Mexican compatriots. Some expatriates had full-time maids, large living quarters, and cooks. These contradictions emerge as self-criticism in the disturbing understated colonial attitudes inherent in The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe.

In his autobiography, Buñuel writes that he “became interested in the story, adding some real and some imaginary elements to Crusoe’s sex life as well as a delirium scene where he sees his father’s spirit.” Characteristically, Buñuel underscores some absurdities in religion with an exchange between Friday and Crusoe, in which Friday seems the more rational. Slowly in the film, Crusoe gives up on his table manners and religious customs which make no sense in the isolation of an island, exposing them as irrational societal conventions. It is only when Friday arrives that Crusoe sees it as his paternalistic duty to teach these same manners and customs to Friday. Unlike the pat definitive Hollywood ending, The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe ends with the surreal barking of Crusoe’s dead dog, harkening to PTSD, delusions or a haunted future. All of these details are characteristically “Buñuel.”

George Pepper co-produced the film with Russian expatriate Oscar Dancigers under the pen-name “George P. Werker” to skirt the blacklist. (It was Dancigers who first talked Buñuel into coming to Mexico to make films.) Defoe’s original novel, Robinson Crusoe, praises the virtues of colonialism, dehumanizing the colonized as mere “savages” and reinforcing a hierarchy between master and slave. Director Luis Buñuel and writer Hugo Butler (aka Philip Ansel Roll) subvert these themes.

Buñuel’s film Las Hurdes was banned in Spain from 1933-1936. Fascism in Spain drove Buñuel to seek work in the United States, only to be subtly blacklisted there as well, before he landed in Mexico. Since Pepper and Butler were blacklisted expatriates as well, the trio’s critique of Defoe’s glorification of conquest is so covert at times, it could be misinterpreted.

Buñuel, Pepper, and Butler’s portrayal of British aristocrat Robinson Crusoe’s shipwreck and isolation on a deserted island echoes the story of the cold war exiles marooned in Mexico. Departing from Defoe, Butler focus on Crusoe’s loneliness, particularly after the death of his dog Rex, as a central theme, echoing the marginalization of the Hollywood exiles. Author and historian Rebecca Schreiber points out, “his entrapment on the island is represented here visually by his inability to walk off the screen.”

The original book begins and ends in Europe, but the film begins and ends on the island. Here, a humanized and often more logical Friday rescues Crusoe from his loneliness and isolation. Also departing from Defoe, the later appearance of some mutineers elicits a comment by Crusoe about the most precious thing in life: community—exactly what enabled the cold war exiles in Mexico to not only survive, but thrive.

Though the internationalist exiles in Mexico often had to hustle and pool resources to make ends meet, they were still better off than their Mexican compatriots. Some expatriates had full-time maids, large living quarters, and cooks. These contradictions emerge as self-criticism in the disturbing understated colonial attitudes inherent in The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe.

In his autobiography, Buñuel writes that he “became interested in the story, adding some real and some imaginary elements to Crusoe’s sex life as well as a delirium scene where he sees his father’s spirit.” Characteristically, Buñuel underscores some absurdities in religion with an exchange between Friday and Crusoe, in which Friday seems the more rational. Slowly in the film, Crusoe gives up on his table manners and religious customs which make no sense in the isolation of an island, exposing them as irrational societal conventions. It is only when Friday arrives that Crusoe sees it as his paternalistic duty to teach these same manners and customs to Friday. Unlike the pat definitive Hollywood ending, The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe ends with the surreal barking of Crusoe’s dead dog, harkening to PTSD, delusions or a haunted future. All of these details are characteristically “Buñuel.”

read more

Buñuel’s film Las Hurdes was banned in Spain from 1933-1936. Fascism in Spain drove Buñuel to seek work in the United States, only to be subtly blacklisted there as well, before he landed in Mexico. Since Pepper and Butler were blacklisted expatriates as well, the trio’s critique of Defoe’s glorification of conquest is so covert at times, it could be misinterpreted.

Buñuel, Pepper, and Butler’s portrayal of British aristocrat Robinson Crusoe’s shipwreck and isolation on a deserted island echoes the story of the cold war exiles marooned in Mexico. Departing from Defoe, Butler focus on Crusoe’s loneliness, particularly after the death of his dog Rex, as a central theme, echoing the marginalization of the Hollywood exiles. Author and historian Rebecca Schreiber points out, “his entrapment on the island is represented here visually by his inability to walk off the screen.”

The original book begins and ends in Europe, but the film begins and ends on the island. Here, a humanized and often more logical Friday rescues Crusoe from his loneliness and isolation. Also departing from Defoe, the later appearance of some mutineers elicits a comment by Crusoe about the most precious thing in life: community—exactly what enabled the cold war exiles in Mexico to not only survive, but thrive.

Though the internationalist exiles in Mexico often had to hustle and pool resources to make ends meet, they were still better off than their Mexican compatriots. Some expatriates had full-time maids, large living quarters, and cooks. These contradictions emerge as self-criticism in the disturbing understated colonial attitudes inherent in The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe.

In his autobiography, Buñuel writes that he “became interested in the story, adding some real and some imaginary elements to Crusoe’s sex life as well as a delirium scene where he sees his father’s spirit.” Characteristically, Buñuel underscores some absurdities in religion with an exchange between Friday and Crusoe, in which Friday seems the more rational. Slowly in the film, Crusoe gives up on his table manners and religious customs which make no sense in the isolation of an island, exposing them as irrational societal conventions. It is only when Friday arrives that Crusoe sees it as his paternalistic duty to teach these same manners and customs to Friday. Unlike the pat definitive Hollywood ending, The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe ends with the surreal barking of Crusoe’s dead dog, harkening to PTSD, delusions or a haunted future. All of these details are characteristically “Buñuel.”

show less

Date/Times:

San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) - closed

800 Chestnut Street, San Francisco, CA 94133

The Best Events

Every Week in Your Inbox

From Our Sponsors

UPCOMING EVENTS

Great suggestion! We'll be in touch.

Event reviewed successfully.