Homegrown: Kelly McFarling

One night every week bars around the world host open mics. These are events in which songwriters–first-timers and veterans–come together, draw names out of a hat (determining the order of performers) and play a tune or two for each other.

[audio:/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/07-Reach.mp3] “Reach” by Kelly McFarling

It’s songwriter roulette, and there are few things more entertaining than the random nature of a well-attended open mic.

All kinds are found at an open mic. For the musician who has sights on becoming the next Bob Dylan (a one-time open mic mainstay in Greenwich Village), the open mic is the initial testing ground; for the neighbor lady who just wants to play a an Emmylou Harris ballad for some people after work, the open mic serves as a weekly gathering centered around an artistic hobby. A cousin of a book club. It’s the first stone on the songwriter’s path, and for some–whether by choice or not–the only stepping stone. It is where love songs, break-up songs, protest songs, grocery list songs (literally a song about what to get at the store), are performed outside of a bedroom for the first time. Anything can happen, especially after midnight.

Because of the unpredictability at the heart of an open mic, it is the most incredible setting to hear someone exceptional. Someone like Kelly McFarling.

There is a hum inherent in an open mic. The bar is filled with musicians and whose primary reason for being there is not necessarily to hear one performer. They are there to perform, to socialize, to network even. Then there are the people at the bar who have no interest in the open mic whatsoever. Glasses are clanked. Orders are called up. Conversations climb on top of one another to be heard. The hum is persistent.

That hum evaporated when I first saw McFarling and her banjo take the Hotel Utah stage in 2007.

I had just started performing songs of my own at the Utah, and so I assumed McFarling was a well-on-her-way musician trying out some new material and cover songs on the local songwriters. Turns out she was in the same position as I was in. The Utah was her first venture into sharing her music, and I am still astounded by this fact. Her voice is sleek, unwavering, and most of all powerful. Just check out her banjo cover of Whitney Houston’s “I Wanna Dance with Somebody” for all the proof you need. Her songwriting is direct, self-deprecating, and confident. In other words, she came off refined before she actually was.

McFarling, originally from Atlanta, Georgia, came out to San Francisco a couple years after finishing up school at Wesleyan University, not to continue a songwriting pursuit, but to start one. That is not to say music and writing were ever far from her thoughts.

“In seventh grade I had a creative writing class that was rooted in writing about your life as a stream-of-conciousness,” McFarling says. “I remember feeling like it was the most important thing I had ever done. I’ve kept a journal for most of my life, and I would attempt poetry in those journals sometimes. I never tried putting those words to music until I moved to San Francisco.”

Long before she ever wrote songs, McFarling was engrossed in musical education. Choir, a capella, and voice lessons filled her time, but the end of school also brought an end to a structured music outlet. For many musicians, it’s a time to move onto the next thing–in other words–either find a regular, entry-level job or putting off said entry-level job and travel. The job starts as something “to pay the bills” while working on that first demo or rehearsing with a newly formed, yet-to-be-named band. Over time, the demo plan becomes more nebulous. The rehearsals become more irregular. There may be a period of heartache, but one moves on.

This transition was not as momentary for McFarling. Singing, she realized, was much more than an extra-curricular.

“I no longer had the choirs and a capella groups and voice lessons. I didn’t know what to do with myself. It was awful. I realized that if I wanted to sing I was going to have to create it myself.”

So, like the rest of us transplants who had artistic notions (or at the very least underlined passages of Ginsberg or Kerouac), she moved to San Francisco. By that point, she had bought the banjo from the window of the music store she walked passed every day and taught herself how to play from lesson books.

“I had always been singing my whole life, and writing my whole life, but I had no instrument that I felt confident with to try and write songs. I was listening to a lot of Gillian Welch at the time — her Soul Journey has some songs where she uses a lovely, haunting claw-hammer banjo, and I fell in love with that sound. I loved how the banjo accompanied the voice, because usually you hear it in bluegrass rolls where it is the primary melodic component. It was kind of an ah-ha moment for me–thinking I could use a banjo to be the accompaniment as opposed to a guitar or piano.”

Although she will always consider herself a vocalist first, McFarling’s choice of the banjo was key.

“It was the catalyst for making the songwriting happen.”

Once in San Francisco, McFarling found the open mic at the Hotel Utah and took to performing banjo-backed covers of the aforementioned Whitney Houston and Michael Jackson. I recall a chuckle coming out of me the moment I recognized the popular songs, but I quickly heard what would become the most distinct trait in McFarling’s own songs. These covers were youthful songs full of young questions, proclamations, and frustrations, all juxtaposed with an “old tyme” instrument. Her performances were fresh and full of conviction.

Similarly, McFarling’s songs are songs of someone setting out, not scouring for a lighthouse. They are songs about the freedom and potential of summer night (“Atlanta”) and what a pain in the ass freedom and blind faith can be (“Fuck New York City”). The banjo I knew before hearing McFarling did not accompany songs with titles like that.

McFarling had filled the void which drove her to San Francisco in large part at the Hotel Utah. “Not knowing a lot of people and not having any expectations of myself made me so wide open to meeting new people and trying new things. It was a huge turning point in my life.”

And that’s the danger about a great open mic. The community surrounding it can be so supportive and comforting that there’s a chance someone with McFarling’s talent never ventures beyond it. A songwriter’s number is always pulled out at the Utah. You always have a place, and unless you play after midnight you always perform for an audience. Those guarantees are gone once you go on tour. The fine folks at a cafe in Manchester, New Hampshire just might not give a damn if you don’t give them a reason to do so, and that’s if they come to the show in the first place. A tour is not a support system. It’s an audition for strangers.

Despite the risk, any musician will say the tour is the only way to make music more than a hobby, however passionate one might be about that hobby, especially in a world where “following” a musician can amount to clicking a button on a Facebook page. The best way for a musician to gain actual fans is to record a collection of songs, then take it to strangers and share a room with them. That will never change. McFarling, who went on her first tour in 2009, couldn’t be happier with this truth and appreciates all the details attached to the unknown musician tour (unknown musician tour — borrow a family member’s van, play cafes with a friend, couch surf,and organize all the details attached to it on your own).

“I love everything about touring because you are on 24/7 with your craft. You are in motion and making things happen, and everything else in your life becomes secondary to what you are doing–which is playing music, and doing all the other things that makes that possible.”

This past March I was in Austin, Texas filming bands at South by Southwest for work. Our company had asked McFarling and other San Francisco bands Con Brio and Sioux City Kid & the Revolutionary Ramblers to play a set at one of our day parties. The night before the show, McFarling and the crew, including bassist Jonathan Kirchner and drummer Andrew Laubacher, ended up camping in the back yard of the house the company was renting. They had been driving for over a week, and the back yard was not flat. They had driven thousands of miles to play a few shows. 30-minute sets (if they were lucky). She was exhausted, but it looked like she was exactly where she wanted to be.

I hope McFarling doesn’t mind me saying this, but 25 is distant in both of our respective rear-view mirrors (I am 29, McFarling is a year or two younger). Having the musician dream is easy when your 20 years old–hell, it’s what you’re supposed to want–but living it, regardless of one’s definition of success, takes balls. When I brought up the age issue, McFarling reminded me Toni Morrison didn’t start writing novels until she was in her forties.

Kelly McFarling has plenty of talent. It was obvious the first time I heard her while waiting for my number to come up at the Hotel Utah. What’s most remarkable is something more universal. When she felt a void, she filled it herself. She taught herself the banjo to fill it. She moved to San Francisco to fill it. She slept in the Austin dirt to fill it, and she probably slept more soundly than most because of it.

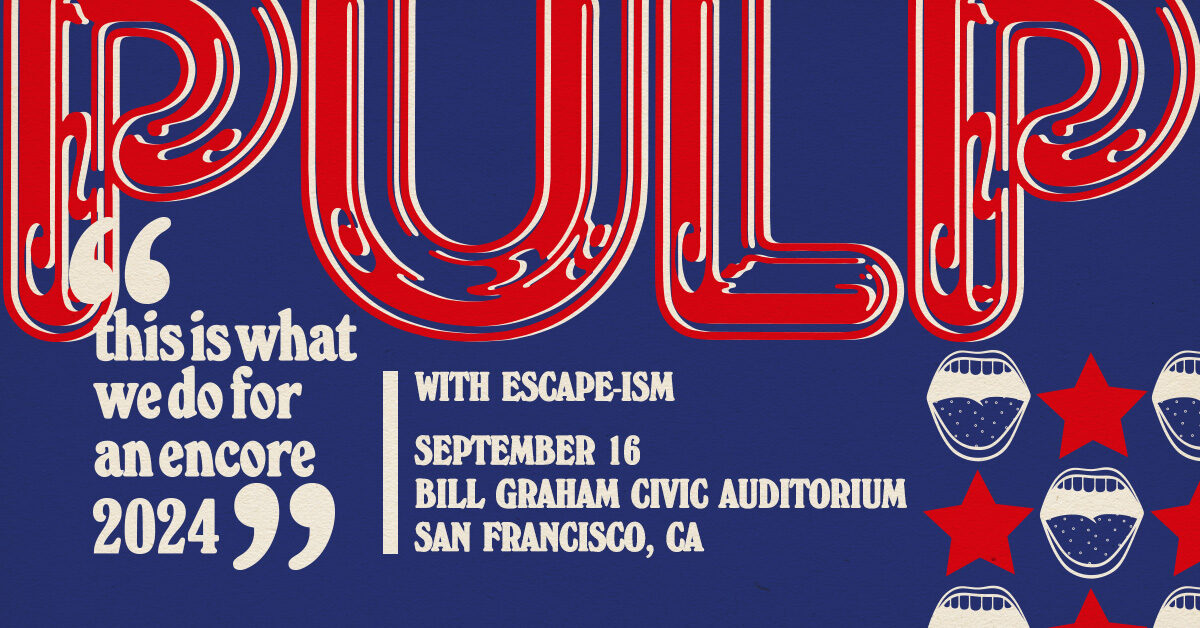

For more info on Kelly McFarling, head over to her website. Do yourself a favor and check her out live tonight (Friday, September 16) at Matching Half in San Francisco at 7PM.

Phil Lang is the Director of Music Operations at BAMM.tv. BAMM.tv curates, produces, and globally distributes performance video content of the best unknown artists. Built by musicians for musicians, BAMM.tv shares net profits 50/50 with the artist through a fair share arrangement that benefits everyone. For more information, email [email protected].

Love the radishes. Love the article.